How to CONTROL your Project’s Things and Money to Deliver the best Results

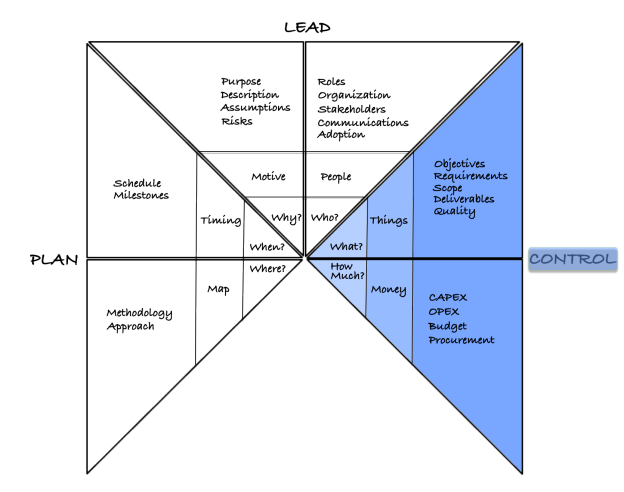

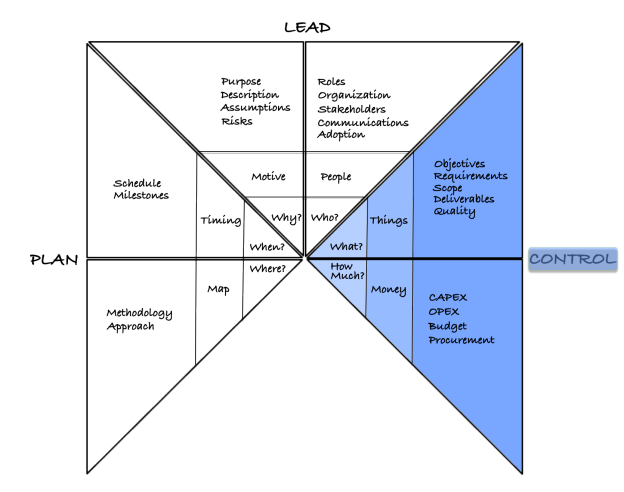

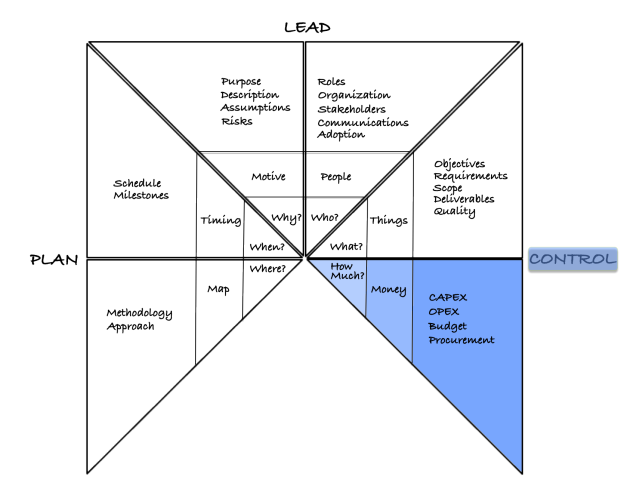

The purpose of this blog post is to cover CONTROL from the MPM model, which is about managing things and money, the outcomes of the project. The CONTROL part is one of the three parts in the MPM model that is performed on a daily and weekly basis during the execution of the project.

The CONTROL part is one of the three parts in the MPM model that is performed on a daily and weekly basis as the project proceeds.

The Project Manager Controls Things and Money

Imagine you have to buy a vehicle and it’s like a small project. And you followed the steps to INITIATE your project, so you have your best start to the greatest probability of project success.

Now weekly you are following the steps to LEAD the Motive and People.

In a few months, you are going to be relaxing with a drink and some delicious appies and thinking, “this was one of the best projects I have ever done thanks to my great project management, if I must say so myself.”

That great project management happened because in addition to LEAD, you daily and weekly used the principles in this blog post to CONTROL the project outcomes and money to achieve a specific purpose. So, let’s get started understanding how to do that.

Follow the weekly steps in CONTROL to ensure you can celebrate your great project management

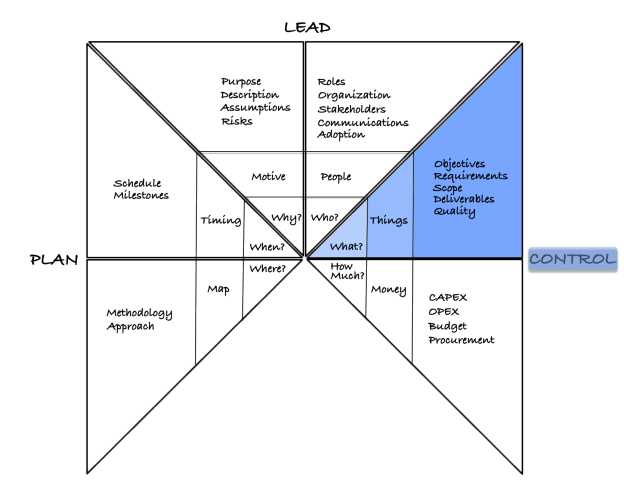

First some context. You completed INITIATE and then your focus turned to LEAD, the first of the middle three parts of the MPM model that contain the daily and weekly habits to successful project management. Those three being: LEAD, CONTROL, and PLAN

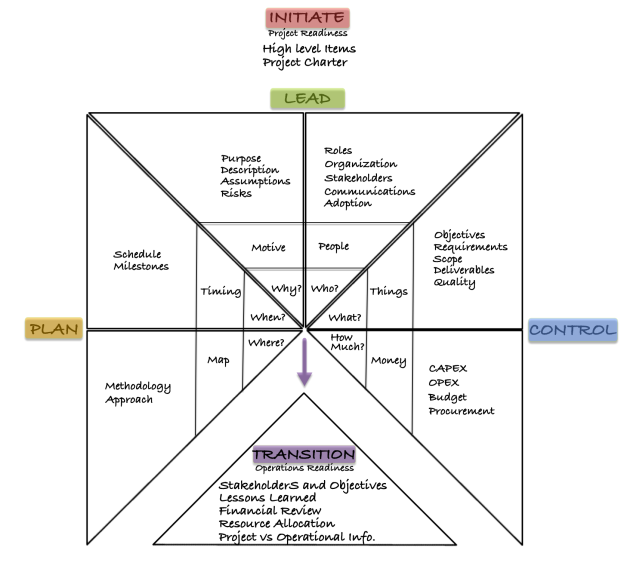

Remember, there are five parts to the model: INITIATE, LEAD, CONTROL, PLAN, and TRANSITION. INITIATE and TRANSITION are the beginning and end, but when the project is in progress, we spend our time in the middle three: LEAD, CONTROL, and PLAN. In this blog post we are covering control. INITIATE was covered in this blog post, and LEAD was covered in this blog post.

CONTROL is about measuring, managing and controlling things and money

Success is small daily and weekly habits

How do you get to that successful end-state, where your deliverables met your requirements, your requirements met your objectives, and they satisfied your purpose, using the least amount of your time?

As with LEAD, CONTROL is about doing specific PM habits each week. They don’t have to take a lot of time, but you need to do them.

Remember one of our goals at Simple PM Strategies is to show you the way to do Project Management using the least amount of your time?

The best way to ensure you’re using the smallest amount of your time is to do some minor activities each week to keep on top of things, to avoid creating major issues that then take more of your time to resolve because they have gotten to a certain point. Make sense?

If you followed the steps in LEAD for the weekly PM habits and activities around Motive and People you found it didn’t take too long, and you helped you feel on top of that part now. Good stuff. Well done.

Your next set of weekly PM tasks is around CONTROL of the Things and Money for your project, the purpose of this article. So, let’s get started.

If you want a refresher on the components of the charter, or why do it in the first place, check out these other articles.

The next section is a quick one-page review of the MPM model to refresh the context of where we are and then we’ll dive into the details of CONTROL.

MPM Model Quick Review

In our project management MPM model, there are 5 parts:

- INITIATE, which involves creating an overview of your project before you get started,

- LEAD, which looks at why you are doing the project and the people that are going to help and be affected by it,

- CONTROL, which is where you shape and manage the outcomes of the project,

- PLAN, which looks at how everything fits together and timing, and

- TRANSITION, which covers how your project outcomes continue to work after the project is done.

Each part of the model always involves all of the other parts as well, but the label for the part tells us our intent at this point, indicates what aspect we are emphasizing, and the lens through which we are looking at our project.

This article then is about the CONTROL part, which is managing and controlling what your project is creating or producing and how much the project is spending.

The project management MPM model has 5 main parts

What is in CONTROL?

CONTROL answers the general questions of “What?” and “How Much?” which for managing projects is “Things” and “Money”.

“Things” are covered in five sections: 1. Objectives, 2. Scope, 3. Requirements, 4. Deliverables, 5. Quality.

“Money” is covered in four sections: REF _Ref65137896 \h 1. CAPEX1. CAPEX, 2. OPEX, 3. Budget, 4. Procurement.

Each section first explains the project item, then brings in the example of the personal vehicle purchase project to help illustrate the concept of the project item and finishes with suggested daily and weekly habits.

A vehicle purchase is a personal example of a project.

Things

The “things” in your project are the tangible portions of whatyou’re accomplishing, producing, and measuring. What I mean is, it’s the things you can touch and feel that someone is willing to exchange for money or other things.

“Things” are what the project is creating

1. Objectives

The objectives are the quantifiable measures directly related to the purpose. In other words, when the project achieves its objectives, it achieves its purpose.

A helpful way to think about objectives is to ask yourself if, at the end of the project, someone else beside you was assessing whether or not the objective was achieved, are the objective statements and the measure of each objective unambiguous enough that anyone could come to the same conclusion?

Objectives need an unambiguous measurement

If not, then revise until it is clear, and the same conclusion could be reached by anyone doing the measuring.

Don’t worry too much about all the acronyms that are out about how they have to be smart, achievable, realistic etc., etc. Just make them unambiguously measurable and you have achieved all of the other aspects that a particular objective needs to exhibit.

Objectives for Your Vehicle Purchase Project

In your vehicle purchase project example, here are some examples of different purposes and possible objectives:

- If my project’s purpose is: Purchase a new vehicle before winter, to use for reliable winter driving, then some objectives could be:

- Objective 1: Buy a new vehicle by October 1.

- Objective 2: Vehicle must have AWD or 4WD.

- If my project’s purpose is: Purchase a vehicle for camping trips to the mountains, then some objectives could be:

- Objective 1: Buy a vehicle by May 1, so that I can be ready for when I go camping in June.

- Objective 2: Vehicle has capacity for camping gear.

- Objective 3: Vehicle can be new or used.

Does achieving your Objectives achieve your Purpose?

If you think through the objectives as achieved and find yourself thinking it may still leave some ways in which your purpose won’t be fulfilled, then add more objectives.

Sometimes it’s helpful to assess your objectives as though they’re independent of your role in the project. This will demonstrate the impact that they have on the outcomes and whether the objectives fit your purpose.

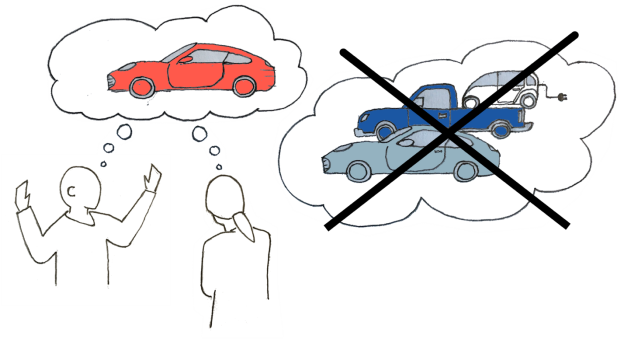

Imagine someone else you know doing your project for you: once you specify your objectives that satisfy your purpose, then you give them complete control of the outcomes they create for your project. If they use the objectives as guidelines, will you be happy with the result?

In other words, your friend uses your objectives, and independently without your input or direction, based only on your objectives, delivers your project end result.

Can your objectives measured by someone else and they get the same result?

Would this work? Is there too much variance in what could be provided? Could something fit those objectives that you wouldn’t be happy with? If you think their completion does not define the satisfactory achievement for your purpose, then add more to tighten them up.

Objectives must be measurable. Notice that in the second example purpose above, new is not specified in that case a used vehicle is acceptable.

Ensure all objectives can be measured objectively and independently by someone other than yourself. Some of objective measures are also binary, either you achieved them, or you didn’t.

To test for measurability, try and apply a numerical value to it, or make sure it can be made into a yes or no question. Examples of detailed measures are described in this article.

Objectives like timelines and costs need to be stated in measurable terms.

A business project is more complicated than our simple example and objectives more difficult to state. However, if they are vague and not measurable, you’ll have a harder time proving what your project accomplished and a harder time keep the team on target if too many things satisfy your objectives.

Make sure your objectives are objectively measurable

If the objectives are too vague, your stakeholders might disagree with your interpretation, and drag out the completion of the project, upping your costs.

Weekly habits for Objectives

Once your Objectives have been defined, they do not need weekly adjustments. Changing or adjusting objectives is always done with caution because it requires stakeholder approvals all over again.

It doesn’t hurt to do a 2-minute weekly review as a reminder of what your requirements and deliverables are working towards as measurable yardsticks.

If they do change, review with your stakeholders because that affects the leadership of your project (as in the LEAD section is affected) because it could impact the achievement of your purpose.

2. Scope

Scope defines the boundaries of your project. You want to specify what is and is not included in your project. Often the motivation for doing scope starts with the need to identify what is out of scope, to clear up misconceptions.

Scope for Your Vehicle Purchase Project

In your vehicle purchase project, some examples could be:

Out of scope:

- Online purchasing – because you want to test drive a vehicle and also check out the local dealerships for service and support.

- Demo models – even if they are considered “new”, you don’t want a demo model. You want to be the first – it’s just something you want.

- Last year’s models – you may only want to look at newer models.

In scope:

- Any dealerships within a 30-minute drive of my current residence or work.

- Any new year models

Scope Items can overlap with other project sections

Scope statements can overlap with your assumptions. For example, you could have a project assumption that states:

- Assume that appropriate vehicle and dealership can be found within a 30-minute radius of home.

Which of course sounds like the first in-scope bullet in the example above, but a little overlap is OK. I have had that before on a number of projects and it has never been an issue with any stakeholders or team members. If it feels like an unnecessary duplication, that becomes obvious and you can remove the duplication.

Start with Out-of-Scope items

Starting the scope section can feel like you’re setting out to the boil the ocean. You’ll feel like you could write pages and pages, but it doesn’t quite work out that way.

If it seems overwhelming, start with what is Out-of-scope first, even though I usually put the In-Scope section first in the charter because it feels more positive. Usually there is more motivation to state what you are not looking at.

Defining scope can feel overwhelming, but is necessary

Create between a half-dozen to a dozen to start with off the top of your head. This isn’t something meant to handcuff you but more to communicate boundaries of what you are looking at to satisfy your requirements.

Handling Changes in Scope

If scope changes do occur, then a formal change management review may be necessary.

This is one of the more challenging areas for project managers and the process can be extensive.

A scope change can sometimes mean that additional money or time is required to complete the project.

In short, if the scope of what is being done increases, including increasing the size or complexity of the deliverables then either something else is reduced or something is added to account for the scope change.

Handling scope change is covered in a separate blog post.

Weekly habits for Scope

Items of in/out-of-scope can change over time if you run into issues in your project. If changes of Scope items do not impact your Project Objectives or Purpose, then you don’t need Stakeholder approval.

This is another item that you can do a quick 2-minute read of once a week.

3. Requirements

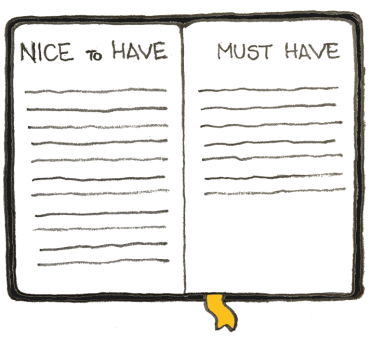

Requirements can be mandatory or optional and can change.

They will most likely change or increase in detail from your charter.

Think of it as a list to help your project team understand what you had in mind for options to satisfy your objectives, but they are more specific and can change.

Requirements for Your Vehicle Purchase Project

In your vehicle purchase project, you might have requirements such as:

- Optional: Preferred color is red

- Optional: Preferred model is an AWD that looks sporty not like a truck

- Optional: Preferred dealerships are on the west end of town because that is directly between work and home

- Mandatory: Not a truck with an open bed

- Mandatory: Not a convertible or soft-top

Weekly habits for Requirements

Requirements definitely change over time. In fact, if your project is large enough or complicated, one of the initial deliverables may be to create a list of requirements.

This is one area you may need to add or update on a weekly basis, but it helps to keep your team and the leadership above you in alignment in terms of options for the deliverables to complete the objectives.

Sometimes it helps to identify optional versus mandatory requirements

True confessions: I have not always kept this area of the project up today, especially if it is changing. Sometimes these are changing as we are brainstorming solutions with the team, and I don’t always go back and update the original list, but it is a good idea – helps with your weekly review.

It is more critical this is kept current for very large projects with many different teams. For smaller projects of a half-dozen dedicated staff, you might find yourself and the team not referencing these as much as the project develops.

However, if you feel it is beneficial because there is a lot of fluidity to the creation of the deliverables and you need some guidelines to circulate to make sure everyone is thinking the same way, then keep a list with three-columns: (1) a unique identifier for the requirement, (2) whether it is optional or mandatory, and then (3) the description of the requirement.

Take 5 to 10 minutes each week to look this over and update as necessary, then do a quick review at your weekly project team meeting and make it accessible to everyone so they can read on their own.

4. Deliverables

Objectives are made up of the achievement of tangible things. We’ll call these things “Deliverables”.

These are the outcomes that achieve your measurable objectives.

Deliverables for Your Vehicle Purchase Project

In our vehicle purchase project example, for some of the first deliverables we can list:

- Price range established

- Vehicle model potentials identified

- Dealerships to visit listed

- Test drives completed

As mentioned in the article on deliverables, describing the deliverables like you’ve already achieved them brings focus to the tasks which produce the deliverables. If you phrase them as an activity, they’re vaguer, and harder to achieve as a result. It’s a key difference.

There is an initial set in the charter, but that can be updated or changed based on working with the team in the beginning, and in the weekly meetings to clarify the deliverables, and the tasks required to achieve them.

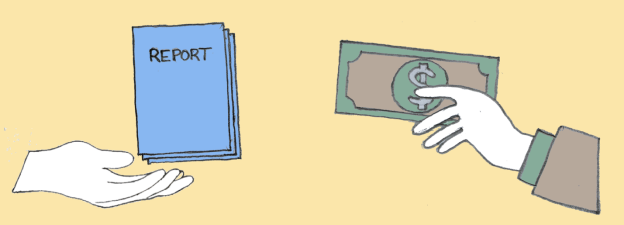

Deliverables are tangible things you can point to, something your client or whomever you are doing the project for, is willing to exchange for money or other things.

Deliverables can be thought of as things you can exchange money for

Tasks, on the other hand, are the actions or activities you take towards completing the deliverable or outcome, and they feel action-oriented.

For more detail about the differences between Deliverables and Tasks – Download a free PDF.

Weekly habits for Deliverables

This is a big one and where you spend most of your time.

On a weekly basis I always do a 15-minute review by myself early in the week to ensure the deliverables we are creating are in line with the Requirements, Objectives, and Purpose.

Why do I do this? Because this is area where you and the team can easily be distracted by shiny objects. (Squirrel!)

When you meet with the team, you are constantly adjusting the tasks that create the deliverables. Sometimes you are also adjusting what the deliverables look like based on what you have been able to accomplish to date and how much time is available in the project for this particular aspect.

There is an old saying in project management. You use eighty percent of the project effort to complete 80% of the deliverables, and to complete the other 20% of the deliverables you use the remaining 80% of the project effort.

That’s why projects are over-budget and late.

This is the most important weekly work you do with your team and sometimes it is a daily discussion.

You discuss what do the deliverables need to look like, and what quality is needed to meet the project objectives.

On a weekly basis, plan to spend about 15 minutes of your own time two to three days a week just looking over what deliverables the project is producing and the status of the tasks that are creating those deliverables.

In your weekly project meeting, this can absorb 45 minutes of a one-hour status meeting. In total you may end up spending two or three hours a week managing the work on the deliverables, including the time discussing in the weekly status meetings, and with individuals and small groups outside of this meeting.

5. Quality

Quality is a gate where the project specifies the tolerance for conformance to requirements for what goes into production or what is finally delivered when the project is completed.

Quality determines what is acceptable for the final solution

In other words, you may have a number of tests for each of your deliverables before you release them as a final solution. This does not mean each deliverable passes all of its tests.

Sometimes it is acceptable to consider the project complete even if the deliverables have defects, to allow them to be “in production” as long as there are no defects which prevent the use of the end result.

Not everything has to be perfect.

This is covered in another blog related to interpretation of quality results.

Quality for Your Vehicle Purchase Project

In our vehicle purchase project, our quality is a little more informal, but it could be something as simple as the example below which covers two tests, their steps, results and status (outcomes):

- Test Name: Dealership XYZ, that has a vehicle I like, is within 30 minutes of home according to online maps.

- Test 1 Steps: Do the drive during the evening

Test 1 Result: 29 minutes door-to-door

Test 1 Status: Passed - Test 2 Steps: Do the drive during rush hour

Test 2 Result: 45 minutes door-to-door

Test 2 Status: Failed – but not blocking. The work around is to only go to the dealership for warrantee work in the evening to drop it off.

You can see now that when you are evaluating the test status you may decide to choose to go with Dealership XYZ even though it failed Test 2, because you can accept the work around.

This is how quality works. You have deliverables or outcomes that require tests to validate the degree of quality. Then the business decides what degree of quality is acceptable.

A failure status does not mean the outcome cannot proceed, or that it is either good or bad, it is just the result in relationship to the test specification.

From a business standpoint you still need to make a decision about whether the outcome of the test is in your range of acceptance.

Weekly habits for Quality

For projects I create a quality tracking sheet that works well for presenting where your quality is at and allows you to make informed decisions about what is acceptable as a gate before going live.

I usually start it and then have others use the same spreadsheet and update it as well.

That is covered in several articles and this one is a good starting point.

Quality distinguishes blocking issues from work-arounds

I review this over for about 5 minutes each week to see where we are at with our quality, especially if there any blocking issues.

The key thing is to run through the tests each time a deliverable is considered complete or each time you have a new version of a deliverable.

Then make your business decision based on the status of the test. Running the tests can take quite a few hours per week, depending on the nature of the tests.

Money

The “money” in your project includes both capital and operational dollars, a presentation of the budget and how procurement takes place on project.

Project Management money covers the type of expense, the budget and procurement for the project

1. CAPEX

CAPEX or Capital Expenses are assets you buy or pay for that have a depreciating value. Your finance, or accounting team, needs these separated from items that cannot be depreciated, the operational expenses (abbreviated as OPEX).

Capital Expenses for Your Vehicle Purchase Project

In the vehicle purchase project, if I buy it, either through a loan or with cash then the purchase is a capital expense.

If I do not buy it, but lease it instead, then it is not capital and is instead an operational expense.

Capital expenses are assets purchased by the project

Weekly habits for Capital Expenses

Capital expenditures usually represent larger, infrequent purchases, so these may only need a review once a month or every few weeks.

If consulting fees are occurring weekly for the implementation of a capital asset and therefore are considered capital expenses, then those hours should have a 15-minute review weekly or bi-weekly as part of project oversight.

2. OPEX

OPEX or Operational expenses are those that occur during the course of operating the project.

These can include for example: consulting dollars, other weekly or monthly administrative, technical, or business expenses.

Project operational expenses are separate from normal operational expenses because the project activities are separate from regular operations activities, as covered in the Initiate blog post. So, the expenses between the two are kept separate.

Your project costs probably appear as a line item on your department’s budget attributed to an identifier for the project, separate from normal operational expenses, so they are a part of the overall budget, just tracked separately.

Operational Expenses for Your Vehicle Purchase Project

For your vehicle purchase project budget, examples of operational expenses can be:

- subscriptions to ratings services

- the cost of transportation to get to the dealership

- the vehicle inspection fee to send to your insurance company, if a used vehicle

Talk to accounting to understand what belongs in CAPEX vs OPEX

Any expenses that you pay after the purchase is completed – monthly insurance payments, tire changes, detailing are all considered non-project operational expenses because the normal operational budget needs to account for these after the project is complete. If you know what those are during the project, keep a separate budget for them to help with future financial projections.

More importantly, a future monthly projected budget maximum amount may be one of your measurable objectives.

Weekly habits for Operational Expenses

Operational expenses can have a 30-minute review bi-weekly or monthly. Depending on how good your corporate finance system is at splitting out and summarizing expenses for projects versus normal operations, this could be an easy summary or a very difficult one.

Review operational expenses for about 30 minutes at least bi-weekly because if there is an error from vendor billing or something being coded incorrectly against your project, it is harder to sort out the longer it goes unchecked.

Usually the operational budget is more active and has many smaller items than the capital budget so the operational expenses may need more frequent attention.

3. Budget

The budget is where the capital and operational dollars are summarized and reviewed against what was expected, the actual, and the forecasted or projected to ensure the project has enough money to complete the deliverables to meet the objectives and satisfy the project purpose within the amount of time remaining.

This is similar to your other management budgets in that you have a separate area for each of the capital and operational expenses. Then individual line items appear underneath each in weekly or monthly buckets proceeding over the timeframe of the project comparing expected, actual and projected.

This is similar to other budgets that you manage.

The project is just like your other budgets, only confined to items within scope for the project

Budget for your Vehicle Purchase Project

The budget for your vehicle purchase includes capital and operational items. Your project also has two kinds of budgets, your project budget and the projected on-going budget after the project is complete. This on-going budget becomes part of normal operations.

Operational expenses can include items that begin during the project and need to continue after and so become part of some department’s on-going operational budget after the project is complete.

How and what to include for capital versus expense items is best left to a discussion between you and your finance team or accountant because each business can operate slightly different. The important thing is to be consistent with whatever policies have been set up for your business.

Find out what that is for your business or talk it over with your accountant. Once you know the rules just follow them.

Weekly habits for Budget

The project budget needs a review at least bi-weekly, or more frequent if there are very active expenditures.

Obtain the policies from accounting for how to handle capital versus operational items and even how to handle the project items versus the post-project operational items.

If very active, review these in a 15-minute call or meeting monthly with your financial team or accountant, and walk through where you made decisions and discuss how you used the policy to put them in the appropriate bucket.

It is always better to be open and transparent with your finance team rather than assume you are making the right decision, and find out later that the mess you made, despite your best intentions requires some extensive corrective journal entries.

That means you’ll be off the Christmas card list from Finance.

4. Procurement

Procurement can cover a range from simple purchases to more complicated RFx purchases.

Project Management procurement covers a range of purchases from simple ones to RFx

RFx includes for example:

- RFI - Request for Information

- RFQ - Request for Quote

- RFP – Request for Proposal

If part of your project is an extensive RFP then there most likely is a procurement procedure you follow for every step in the process including: Creating, Advertising/Soliciting, Managing, Evaluating, Awarding, Contracting, Procuring.

Procurement in the Vehicle Purchase Project

An RFx is not likely part of your vehicle purchase project unless you are buying a fleet of vehicles.

In the vehicle purchase project your purchase is based on your decision and it does not need a lot of other paperwork.

Weekly Habits for Procurement

If you have an extensive procurement exercise as part of your busines project, such as the cycle for an RFP then this involves daily activities until the contract is signed and procurement commences.

Once there is a contract in place, procurement starts and follows the contract terms and conditions. The weekly review of purchases against the contract then follows your review of either capital or operational expenses.

Summary

Managing and controlling things your project is producing and the money that is being spent, the “what” and “how much” requires a lot of detailed analysis and review on a weekly basis.

Project deliverables need weekly review and oversight as this is where most of the project out-of-scope or over-budget for time or money originates.

This is the area that needs the most project management attention and it comes in the form of weekly review of what is being delivered and how it is meeting the project objectives.

Meeting the project objectives involves balancing an increase in effort for some deliverables with a decrease in effort on other deliverables as long as the project objectives are being met.

Action Steps / Apply This Knowledge

- Create a review sequence or checklist for early in the week which includes a cursory review of some items and a more in-depth review of others. Attempt to keep the review to under 60 minutes or the risk is that you’ll skip it on some weeks.

- In the weekly review of things and money, alternate weeks with items that require more time to keep the review time to an hour.

- Bring that review schedule into the weekly project team meeting, ensuring that if tasks that take longer than expected, are appropriate for meeting the project objectives, and if so, then where can the project reduce effort or change assumptions about the order or sequence in which deliverables are completed to save time and keep the project on time and budget.

Learn More

In an upcoming workshop, for which you can subscribe to be notified when it’s available, we cover project management examples in detail.

Also, in the workshop, we go into greater depth on many of the project management items in the Manager Project Mastery (MPM) model. As well you can ask questions about any of your current projects during the Q&A.

CONTROL - Main

© Simple PM Strategies 2021